What Is Stockholm Syndrome?

The term was coined by the criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot to explain the aftermath of a bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden in 1973.

It is not a psychological diagnosis, but a way to describe and understand the responses some hostages have towards their captures.

The bond that some hostages create with their captures may seem irrational but may include feelings of love, sympathy, empathy, and s desire to protect their captures.

It is not clear why some people react this way, but it is thought to be a survival mechanism. A person can develop these bonds as a way to cope with an extreme and terrifying situation. Some factors can increase the possibility for such bonds to develop such as;

- Being in an emotionally charged situation for a _long_ time.

- Being in a shared space with the capturer in poor conditions

- If the hostages are dependent on their capturer for all their basic needs

- If threats to the hostages’ lives are not carried out

- When hostages haven’t been dehumanized

Some also think that the Stockholm syndrome only will appear if the hostage and capturer have no previous relationship between them.

Experts have agreed on three characteristics that must be displayed in victims of hostage situations

- Hostages must display positive feelings towards their captors

- Hostages have negative feelings, like fear, distrust, or anger, toward the authorities

- The captors must display positive feelings towards the hostages

According to the FBI 73 % of hostages do not show any signs of Stockholm syndrome, they may express anger towards authorities, but do not show positive feelings towards their captors.

The term Stockholm syndrome is the name for a psychological response to captivity and abuse. A person with Stockholm syndrome develops positive associations with their captors or abusers. Experts do not fully understand this response formation but think it may serve as a coping mechanism for people who experience trauma.

A person can develop Stockholm syndrome when they experience significant threats to their physical or psychological well-being.

A kidnapped person may develop positive associations with their captors if they have face-to-face contact with them.

If the person has experienced physical abuse from their captor, they may feel gratitude when the abuser treats them humanely or does not physically harm them.

A person may also attempt to appease an abuser in order to secure their safety. This strategy can positively reinforce the idea that they might be better off working with an abuser or captor. This could be another factor behind the development of Stockholm syndrome.

Although Stockholm syndrome was named based on the location of a bank robbery-hostage situation, some of the same behaviors and feelings are seen in victims of other types of trauma, including:

Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse.

Child abuse.

Human sex trafficking.

With all this in mind let’s now take a look at the incident that minted the expression.

The Bank robbery

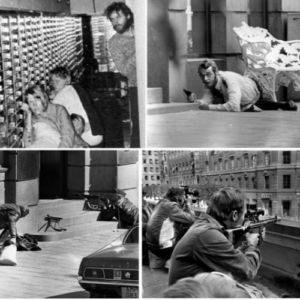

On the morning of August 23, 1973, an escaped convict crossed the streets of Sweden’s capital city and entered a bustling bank, the Sveriges Kreditbanken, on Stockholm’s upscale Norrmalmstorg square. From underneath the folded jacket he carried in his arms, Jan-Erik Olsson pulled a loaded submachine gun, fired at the ceiling, and, disguising his voice to sound like an American, cried out in English, “The party has just begun!”

After wounding a policeman who had responded to a silent alarm, the robber took four bank employees hostage. Olsson, a safe-cracker who failed to return to prison after a furlough from his three-year sentence for grand larceny, demanded more than $700,000 in Swedish and foreign currency, a getaway car, and the release of Clark Olofsson, who was serving time for armed robbery and acting as an accessory in the 1966 murder of a police officer. Within hours, the police delivered Olsson’s fellow convict, the ransom, and even a blue Ford Mustang with a full tank of gas. However, authorities refused the robber’s demand to leave with the hostages in tow to ensure safe passage.

The unfolding drama captured headlines around the world and played out on television screens across Sweden. The public flooded police headquarters with suggestions for ending the standoff that ranged from a concert of religious tunes by a Salvation Army band to sending in a swarm of angry bees to sting the perpetrators into submission.

Holed up inside a cramped bank vault, the captives quickly forged a strange bond with their abductors. Olsson draped a wool jacket over the shoulders of hostage Kristin Enmark when she began to shiver, soothed her when she had a bad dream, and gave her a bullet from his gun as a keepsake. The gunman consoled captive Birgitta Lundblad when she couldn’t reach her family by phone and told her, “Try again; don’t give up.”

When hostage Elisabeth Oldgren complained of claustrophobia, he allowed her to walk outside the vault attached to a 30-foot rope, and Oldgren told The New Yorker a year later that although leashed, “I remember thinking he was very kind to allow me to leave the vault.” Olsson’s benevolent acts curried the sympathy of his hostages. “When he treated us well,” said lone male hostage Sven Safstrom, “we could think of him as an emergency God.”

By the second day, the hostages were on a first-name basis with their captors, and they started to fear the police more than their abductors. When the police commissioner was allowed inside to inspect the hostages’ health, he noticed that the captives appeared hostile to him but relaxed and jovial with the gunmen. The police chief told the press that he doubted the gunmen would harm the hostages because they had developed a “rather relaxed relationship.”

Enmark even phoned Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, already preoccupied with looming national elections and a deathbed vigil for the country’s revered 90-year-old King Gustaf VI Adolf, and pleaded with him to let the robbers take her with them in the escape car. “I fully trust Clark and the robber,” she assured Palme. “I am not desperate. They haven’t done a thing to us. On the contrary, they have been very nice. But, you know, Olof, what I am scared of is that the police will attack and cause us to die.”

Even when threatened with physical harm, the hostages still saw compassion in their abductors. After Olsson threatened to shoot Safstrom in the leg to shake up the police, the hostage recounted to The New Yorker, “How kind I thought he was for saying it was just my leg he would shoot.” Enmark tried to convince her fellow hostage to take the bullet: “But Sven, it’s just in the leg.”

Ultimately, the convicts did no physical harm to the hostages, and on the night of August 28, after more than 130 hours, the police pumped teargas into the vault, and the perpetrators quickly surrendered. The police called for the hostages to come out first, but the four captives, protecting their abductors to the very end, refused. Enmark yelled, “No, Jan and Clark go first—you’ll gun them down if we do!”

In the doorway of the vault, the convicts and hostages embraced, kissed, and shook hands. As the police seized the gunmen, two female hostages cried, “Don’t hurt them—they didn’t harm us.” While Enmark was wheeled away in a stretcher, she shouted to the handcuffed Olofsson, “Clark, I will see you again.”

The hostages’ seemingly irrational attachment to their captors perplexed the public and the police, who even investigated whether Enmark had plotted the robbery with Olofsson. The captives were confused, too. The day following her release, Oldgren asked a psychiatrist, “Is there something wrong with me? Why don’t I hate them?”

Psychiatrists compared the behavior to the wartime shell shock exhibited by soldiers and explained that the hostages became emotionally indebted to their abductors, and not the police, for being spared death.

Even after Olofsson and Olsson returned to prison, the hostages made jailhouse visits to their former captors. An appeals court overturned Olofsson’s conviction, but Olsson spent years behind bars before being released in 1980. Once freed, he married one of the many women who sent him admiring letters while incarcerated, moved to Thailand, and in 2009 released his

released his autobiography, entitled Stockholm Syndrome.

But as I said the connections went both ways, and as Olsson has said in an interview with American journalist Daniel Lang ‘It was the hostages’ fault, they did everything I told them to do. If they hadn’t, I might not be here now. Why didn’t any of them attack me? They made it hard to kill. They made us go on living together day after day, like goats, in that filth. There was nothing to do but get to know each other.”

There have been many famous cases, both before and after the incidents in Stockholm that can be attributed to Stockholm syndrome. Here are four examples, and you may decide for yourself if Stockholm syndrome is an accurate description.

Famous cases

Patty Hearst

On February 4, 1974, Patty Hearst, the 19-year-old granddaughter of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, is kidnapped from her apartment in Berkeley, California, by three armed strangers. Her fiance, Stephen Weed, was beaten and tied up along with a neighbor who tried to help. Witnesses reported seeing a struggling Hearst being carried away blindfolded, and she was put in the trunk of a car. Neighbors who came out into the street were forced to take cover after the kidnappers fired their guns to cover their escape.

Three days later, the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a small U.S. leftist group, announced in a letter to a Berkeley radio station that it was holding Hearst as a “prisoner of war.” Four days later, the SLA demanded that the Hearst family give $70 in foodstuffs to every needy person from Santa Rosa to Los Angeles. This done, said the SLA, negotiation would begin for the return of Patricia Hearst. Randolph Hearst hesitantly gave away some $2 million worth of food.

The SLA then called this inadequate and asked for $6 million more. The Hearst Corporation said it would donate the additional sum if Patty was released unharmed.

In April, however, the situation changed dramatically when a surveillance camera took a photo of Hearst participating in an armed robbery of a San Francisco bank, and she was also spotted during a robbery of a Los Angeles store. She later declared, in a tape sent to the authorities, that she had joined the SLA of her own free will.

According to Jeffrey Toobin, the author of American Heiress The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst

“ My view of Patricia’s story is that she responded rationally to the circumstances she was confronted with at each stage of the process. She was 19 years old, she was being treated well by the SLA, she was being told that her family and the FBI were abandoning her, and she did, in fact, join with them.”

On May 17, Los Angeles police raided the SLA’s secret headquarters, killing six of the group’s nine known members. Patty Hearst and two other SLA members wanted for the April bank robbery were not on the premises.

Finally, on September 18, 1975, after crisscrossing the country with her captors—or conspirators—for more than a year, Hearst, or “Tania” as she called herself, was captured in a San Francisco apartment and arrested for armed robbery. Despite her claim that she had been brainwashed by the SLA, she was convicted on March 20, 1976, and sentenced to seven years in prison. She served 21 months before her sentence was commuted by President Carter. After leaving prison, she returned to a more routine existence and later married her bodyguard. She was pardoned by President Clinton in January 2001.

Colleen Stan

Just three years after Patty Hearst was kidnapped, 20-year-old Colleen Stan underwent a horrifically brutal ordeal, resulting in another infamous case of Stockholm syndrome.

On May 19, 1977, Stan set out to hitchhike to a friend’s party close to Red Bluff, California. Soon, Cameron Hooker and his wife, Jan, offered her a ride. Since the couple had a young child, Stan assumed she would be safe. However, aided by Jan, Hooker kidnapped Stan to be his sex slave.

Stan was held captive for seven years, during which time she was raped, tortured, and kept in a coffin-like box for 22–23 hours a day. In 1978, Hooker forced her to “sign herself” into sex slavery. Her name became “K,” and Hooker even referred to her as a piece of furniture, only allowing her to call him “Master.”

Hooker convinced Stan that he was part of an organization known as “The Company,” and that they would hurt Stan and kill her family if she did not obey his every command. Stan was so deeply influenced by Hooker that when he told her to put a gun in her mouth and pull the trigger, she complied. However, the act was said to be a test of loyalty because there were no bullets in the gun.

Four years after the kidnapping, in 1981, Hooker took Stan to visit her family and even left her alone with them overnight. Her family was unaware of the circumstances, and Stan never told them. Instead, she said Hooker was her boyfriend and claimed to be happy with him, even taking a picture the next day when he picked her up.

Stan remained with the Hookers for another three and a half years. In 1985, consumed by guilt, Jan finally helped Stan escape. Hooker was convicted of torture and kidnapping and sentenced to 104 years in prison. The FBI later said Stan’s case was “unparalleled in its brutality.” The mental and physical torture she was subjected to caused her to mentally break in order to cope and survive.

Even with an open door, neighbors, and a telephone, Stan made no attempt to escape; she said that her fear of The Company kept her from seeking help.

For years, neighbors believed she was just the family’s helper.

Jaycee Dugard

On June 10, 1991, 11-year-old Jaycee Lee Dugard was kidnapped by Phillip Greg Garrido in front of her stepfather’s eyes. Though he tried to save her, he could not keep up with Garrido’s car as it sped away.

Dugard was held captive for nearly 18 years until 2009. Garrido and his wife, Nancy, abused and imprisoned Dugard, forcing her to live in a shed in their yard. Garrido told Dugard that “demon angels” let him kidnap her because she was supposed to “help” him with his society-condemned “sexual problems” (child molestation and rape).

During her captivity, Dugard had two daughters fathered by Garrido. They were both born with no medical care and never had the opportunity to go to school. Instead, they were educated at home by Dugard and educational TV shows. Many psychiatrists believe that because they had children together, in Dugard’s mind (at least during her captivity), her relationship with Garrido was a type of marriage-like relationship.

Eventually, Dugard began helping Garrido with his business by answering calls and emails. Some people later claimed they had seen her off the property, but Dugard insisted she had never left. She also seemingly never tried to escape or share her true identity.

Eventually, suspicions arose, and police showed up to investigate Garrido. Dugard met with them and introduced herself as “Alissa,” the false identity Garrido gave her. She defended Garrido and acknowledged that while he was a known sex offender, he was “good with her kids” and was a “changed man.” Dugard was defensive when being questioned and lied to protect Garrido, stating that she was staying with Garrido while hiding from her abusive husband. One officer at the scene, Ally Jacobs, observed that Dugard’s daughters, then 15 and 11, seemed to be “brainwashed zombies.”

Dugard eventually revealed her identity, Garrido was arrested, and Dugard was reunited with her family. She shared that she felt a deep emotional connection with Garrido but later denounced his actions and stated, “I adapted to survive my circumstances.” Dugard has never spoken about Stockholm syndrome specifically, but experts believe it was her means of survival.

Mariano Querol

The case of Mariano Querol is one of the more fascinating cases of Stockholm Syndrome, as Querol, a Peruvian psychiatrist, analyzed the situation himself after the fact.

In 1996, the 71-year-old was kidnapped and held captive for 18 days by a group of four middle-class men led by Gonzalo Higueras, a 43-year-old businessman who was the neighbor of one of Querol’s children. Higueras was in financial trouble and wanted to use ransom money for Querol to pay his rent and the boarding school tuition of his children.

Querol quickly bonded with his captors, eventually asking them to let him listen to music, allow him to eat more vegetables, and bring him books to read, all of which the kidnappers complied with. They even watched TV and began reading books together, most notably “News of a Kidnapping” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which centered on a kidnapping much like the one they were currently partaking in.

Additionally, Querol began giving his captors counseling sessions, building sympathy for them. His main captor, who he called “mi amigo” even confided in Querol about his anxiety regarding the kidnapping. Querol’s family paid the $150,000 ransom, and Querol was released unharmed. When they left him in the street, “mi amigo” gave him money for a taxi.

Higueras was captured almost immediately. Querol admitted to being scared for his life before he was released, but he still asked for reduced sentences for all his captors. He admitted to knowing he had Stockholm syndrome but felt like there was an extra layer in his particular case.

Experts believe Querol’s bond with his captors saved his life. He knew their identities, yet they let him live, which is atypical for ransom situations.