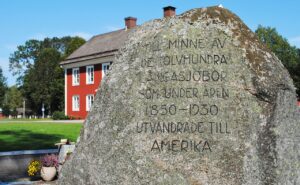

How many Swedes emigrated?

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the mass emigration of some 1.3 million Swedes to the United States occurred.

Why did they leave?

Emigration was due to several reasons. One was the sharp population growth. Between 1825 and 1900, the number of children born yearly doubled. The difficult living conditions in cities and the countryside were also important reasons people chose to leave Sweden. The 1850s editions of Contributions to Sweden’s official statistics begin with a five-year report from Tabellkommissionen that describes the situation in the country in a vibrant style concerning the weather, the harvests, and epidemics.

The introduction for 1851-55 begins: “As regards climate, 1851 was marked by a cold and rainy summer with a high water level. The annual harvest in the country was estimated to be small rather than average and was also marked in many places by damage from ergot fungi and other parasites, a lack of growth, and bad weather.”

Most of Sweden’s population lived in the countryside at this time. The population in Sweden was 3 482 541 persons in 1850, of whom 3 131 015, or close to 90 percent, lived in the countryside. The city of Stockholm had a population of 93 070 persons or about 2.5 percent of Sweden’s population.

At the same time, several epidemics raged, such as cholera, dysentery, smallpox, and typhus. Cholera was the worst epidemic and took the lives of 26 413 persons. Stockholm was hard hit and lost 7 745 inhabitants. Dysentery was the cause of 7 542 deaths, while 6 347 persons succumbed to smallpox from 1847 to 1855.

Where did they move?

As a result of immigration, the population group in the United States of Swedish extraction was thus well over one million during the first decades of the twentieth century. However, it was not evenly distributed throughout the country. The early phase of Swedish immigration established the Midwestern states as a prime receiving area. The agricultural areas in western Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and western Wisconsin formed the nucleus of the first Swedish settlements. Migration chains were quickly established between many places in the Midwest and in Sweden, encouraging and sustaining further movement across the Atlantic. After the Civil War, the Swedish settlements spread further west to Kansas and Nebraska, and in 1870 almost 75 percent of the Swedish immigrants in the United States were found in Illinois, Minnesota, Kansas, Wisconsin, and Nebraska.

By 1910 the position of the Midwest as a residence for the Swedish immigrants and their children was still strong but had weakened. Fifty-four percent of the Swedish immigrants and their children now lived in these states, with Minnesota and Illinois dominating. Fifteen percent lived in the East, where the immigrants were drawn to industrial areas in New England. New York City and Worcester, Massachusetts, were two leading destinations. A sizeable Swedish-American community had also been established on the West Coast, and in 1910 almost 10 percent of all Swedish-Americans lived there. There, the states of Washington and California had the largest Swedish-American communities. In Washington, a heavy concentration of Swedish Americans grew up in the Seattle-Tacoma area.

Minnesota became the most Swedish of all states, with Swedish Americans constituting more than 12 percent of Minnesota’s population in 1910. If Minnesota became the most Swedish state in the union, the city of Chicago would be the Swedish American capital. In 1910, more than 100,000 Swedish Americans resided in Chicago, meaning about 10 percent of all Swedish Americans lived there. At the turn of the century, Chicago was also the second-largest Swedish city in the world; only Stockholm had more Swedish inhabitants than Chicago.

Swedes in America

Swedish mass immigration to the U.S. began in earnest in the mid-1840s, when several pioneers, often moving as groups, established a migration tradition between certain sending areas in Sweden and particular receiving locales in the United States. Examples of colonies founded by these groups include settlements in western Illinois, Iowa, central Texas, southern Minnesota, and western Wisconsin.

When the American Civil War broke out, ending the pioneer period of Swedish immigration, the federal Census recorded some 18,000 Swedish-born persons in the United States. Ten years later, following the first heavy peaks of Swedish immigration in 1868-69, largely due to crop failures in Sweden, the figure was almost five times higher, or 97,332. The rapid increase in Swedish immigration continued. By 1890, following the single decade of the largest Swedish immigration, approximately 478,000 Swedes lived in the United States. During the 1880s alone, some 330,000 persons left Sweden for the United States, the peak year being 1887, with over 46,000 registered emigrants.

The pace of immigration remained high after 1890, and by 1910, the U.S. Census recorded over 665,000 Swedish-born persons in the United States. Just as the Civil War had restricted the number of foreigners who could enter the United States, World War I curtailed the number of immigrants during the 1910s, and by 1920 the number of Swedish-born in the United States declined for the first time, the total population standing at 625,000. The year 1923, when over 26,000 Swedes left for the United States, represents the end of some eight decades of sustained mass migration from Sweden to the United States.

From 1851 to 1910, roughly one million people emigrated from Sweden to America. Of those born during the latter part of the 19th century, about 20 percent of the men and 15 percent of the women emigrated from the country.

Swedish American culture

Svenskamerika, or Swedish America, as the Swedish American community began to be referred to around 1900, was a collective description of the cultural and religious traditions that the Swedish immigrants brought to their new homeland. These traditions were both preserved and changed through interaction with American society. They formed the basis for the sense of Swedishness or Swedish-American identity that developed among the immigrants and their descendants.

Swedish America was split culturally, religiously, and socially. By the beginning of the twentieth century, different Swedish-American institutions, such as churches, organizations, associations, and clubs, formed an intricate pattern that spanned the entire American continent. The largest organizations were the various religious denominations founded by Swedish immigrants in the United States.

The secular organizations attracted fewer members. The mutual-aid societies include the Vasa Order, the Svithiod Order, the Viking Order, and the Scandinavian Fraternity of America.

A cultural life quickly developed within the Swedish-American community. Much of it was centered on the Swedish language, which was a key factor in the culture’s creation and maintenance. The Swedish-language press played an important role in this respect, and it has been estimated that between 600 and 1,000 Swedish-language newspapers were published in the United States.

Midsummer celebrations occurred as early as the 1870s and had become quite common by 1900, often filling the function of a Swedish or Swedish-American national day. It is no coincidence that Svenskarnas Dag in Minneapolis has been celebrated in the middle of June since 1934.

Even though predictions of the demise of the Swedish-American community have been heard ever since Swedish mass immigration to the United States came to a halt in the 1920s, some four million persons still responded “Swedish” to the question of their ancestry in the 2000 U.S. Census. Swedish America today overwhelmingly consists of descendants of Swedish immigrants, many of whom are by now in the third generation and beyond.

Expressions of Swedishness today often focus on family history, foods, and holiday celebrations but also on an interest in traveling to Sweden and sometimes on learning about modern Sweden and the Swedish language.

The great emigration in books and movies

Vilhelm Moberg was born in 1898 in Småland, in the south of Sweden. He was the fourth child in a family of seven kids. He led a harsh and simple childhood and, early on, found an interest in the literary world. He was best known for his novels about the Swedish emigration to America but concerned primarily with the people of the countryside from which he came and with the system that made life so miserable for them.

The Emigrants is the collective name of a series of four novels by him

The Emigrants (Swedish: Utvandrarna), 1949

Unto a Good Land (title in Swedish: Invandrarna ‘The Immigrants’), 1952

The Settlers (Swedish. : Nybyggarna), 1956

The Last Letter Home (title in Swedish: Sista brevet till Sverige ‘The Last Letter to Sweden’), 1959he

All the books have been translated into English.

The novel series describes the long and strenuous journey of a party of emigrants from the province of Småland, Sweden, to the United States in 1850, coinciding with the beginning of the first significant wave of immigration to the United Statesfda, from Sweden. The story focuses primarily on Karl-Oskar Nilsson and his wife, Kristina Johansdotter, a young married couple who live with their four small children; Anna, Johan, Lill-Märta, and Harald, as well as Karl-Oskar’s parents and his rebellious younger brother Robert, who works as a hired farmhand for neighboring farmers.

The family lives on a small farm at Korpamoen, where the soil is thin and rocky, making growing crops difficult. It is Robert, with his friend Arvid, who first comes across the prospect of going to America after being tired of being mistreated by the farmers who employ him. When he confronts Karl-Oskar about the idea, Karl-Oskar reveals that he, too, has come across pamphlets describing conditions in North America for farmers as being much better.

Kristina, however, is against emigrating, not wanting to leave her homeland or wanting to risk the lives of her children by taking them across the ocean. However, things take yet another tragic turn for the family, which causes Kristina to reconsider.

These novels have also become movies;

The Emigrants (Swedish: Utvandrarna) is a 1971 Swedish film directed and co-written by Jan Troell and starring Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Eddie Axberg, Allan Edwall, Monica Zetterlund, and Pierre Lindstedt.

his film adapts the first two of the four novels (The Emigrants and Unto a Good Land), depicting the hardships the emigrants experience in Sweden and their journey to America.

The New Land (Swedish: Nybyggarna) is a 1972 Swedish film directed and co-written by Jan Troell and starring Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Eddie Axberg, Allan Edwall, Monica Zetterlund, and Pierre Lindstedt. It and its 1971 predecessor, The Emigrants (Utvandrarna), were produced concurrently.

This film adapts the latter half of the four novels (The Settlers and The Last Letter Home), which depict the struggles of the immigrants to establish a settlement in the wilderness and adjust to life in America.

Both movies have been nominated for and won several awards around the world.

The Emigrants was filmed again in 2021 in Sweden by director Eric Poppe.